Now is the time to focus on inclusive community supports and better care systems that will benefit us all.

In the 1980’s, it was still common practice to advise families with children diagnosed with disabilities, no matter how mild or severe, to place them in a institutions and children’s homes that doctors believed would be better equipped to meet their medical, physical and social needs.

My family had gone to a clinic through children’s rehab services and funded by the Shriner’s and this was the advice that we were given when I was diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy at age 2.

Grandpa Keelan, a Navy Veteran could not understand why the services, could not be performed in our home and why my disability should be a reason to take me from my family.

Me and Grandpa Keelan 1982, in Congress Junction, AZ. This is where I learned to stand by hanging onto furniture like my playpen.

My family always believed that my disability wasn’t the problem, but the real barriers were both physical and attitudinal and that separating me from my family would cause more emotional harm than good. At that time period, there were no alternatives-- if you wanted services: medical, therapy and equipment, it could only be obtained in an institutional setting. So, we said NO THANKS, we will create our own therapy programs, mobility devices and ramps. The moral, medical and financial models of disability were quite common. And my family continued to fight for my right to live and receive services in my home and community despite the push back and threats of neglect and abuse made by agencies and medical doctors who were more concerned with the control of the financial resources than my social well-being.

July 2021 Neighborhood Social Media Post:

The posting went something like this: “Hi, I need recommendations for a 24/7 nursing home facility for a 27-year-old that is wheelchair bound with…”.

The posting went on to describe in intimate detail, what services were needed, as if the information had been taken from a personal care plan, and also included that the person was already receiving home health care, Medicaid and social security disability. It was stated that the person is “very smart, but it is difficult to find a place who will take someone of this age”.

The neighborhood’s response was even worse, more like a mob mentality by the community, suggesting nursing homes and care facilities, places where neighbors had sent their parents or siblings, and even suggestions by health care professionals who should have recognized the obvious HIPPA and Patient Privacy Act violations that were occurring before their eyes. Their discussions were not only in an open forum but were demoralizing and demeaning. The community had decided this person’s fate- site unseen and no one cared enough to say: “What does the person who is capable of making their own decisions want?”

Besides setting a dangerous precedence for people with disabilities who live in the community and receive services that support their independence, the comments are reinforcing negative stereo types about people with disabilities and it is clear that the person who is wheelchair bound, is being exploited and it was being done possibly by a family member, apartment manager or neighbor. Maybe my neighbor or your neighbor. This scenario brought out a flood of personal memories of negative experiences, memories of housing property managers making accommodations about me, without my knowledge or consent, in an effort to move me out of the community and this is occurring on a regular basis across America.

One of the many important purposes of the ADA, focused on community integration and the Olmstead Act and the right to make personal choices, to have a voice. I know this because my family gave testimony to the Task Force when they were putting together the ADA diaries back in the late 1980’s. I remember the interviewer transcribing our experiences with discrimination and the emotional scars it left behind, stories shared by my Mom, sister and myself. Experiences with loss of jobs, education, forced experimental surgeries, threats of noncompliance and loss of services and loss of housing.

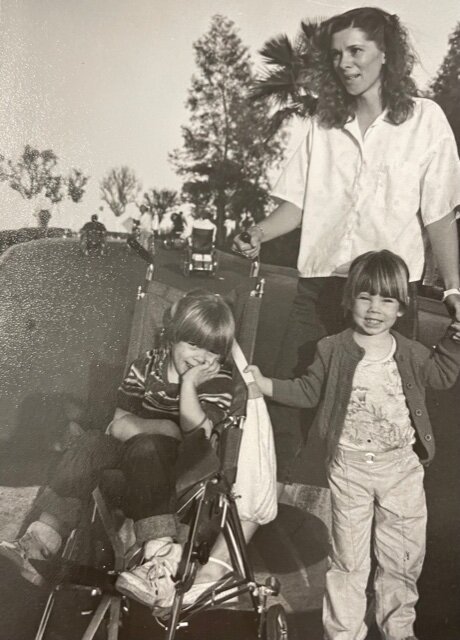

My first protest in Phoenix, Arizona, before I got my first wheelchair. ( Me, Kailee and Mom). 1987

Yet 31 years later, society is still making decisions about us from the moral, medical and financial models and outdated policies that are more beneficial financially to the agencies than to the people the program is supposed to assist and as if we are unable to know what is best for ourselves or that our “care” can only be obtained in a facility. Geez, I wish I had a dollar for every time an agency told me that bars in the bathroom and wheelchair access are only available in nursing homes!

In Seven Core Arguments of Disability Rights, Andrew Pulrang writes:

“There is a crucial difference between services that support disabled people’s needs, wishes and priorities through assistance and empowerment—and services that protect and maintain disabled people through sheltering and control.”

When people generally think of barriers, they think of the obvious—the lack of physical access but people often do not realize that there are attitudinal barriers that are often more harmful and yes folks-that is discrimination. Some people think if they target the caregiver, parents, home health aides and the service dog, that is it is not discrimination, but I remember my Mom talking at length with the Task Force interviewer about the need for protections under “association discrimination” and I think it may be hidden somewhere in the ADA but is greatly ignored.

One of the most impressive protests for me as a child was the “Wheels of Justice March” in March of 1990.

From all across America, families, veterans, politicians, advocates, activists, civil rights and disability organizations, all came together to speak with a unified voice for the purpose of getting the ADA passed without any further delay or weakening amendments.

Together, we pressured Congress to recognize the importance of the ADA and the importance of Disability Justice! We were powerful and we empowered each other.

We need that now in our communities and it will benefit everyone. We need to build allies and community support. We need to empower each other and fight together.

“NOW is the time for Unified Voices for Disability Justice” Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins

In loving memory of my sister, Kailee Keelan who died on July 20, 1993.

She was a true activist and ally for disability rights.